Shot on large-format 68mm negatives and at a much higher frame rate than other early films, these very brief vignettes have a staggering clarity and richness of detail. In January 2019, the Museum of Modern Art presented two programs of Biograph films made between 18, one presented by the British Film Institute and the other from MoMA’s own collection. She suggests that railroads, born around the same time as still photography, “prepared viewers for the kinds of visual experience that cinema would make ordinary, it had adjusted people to a pure visual experience stripped of smell, sound, threat, tactility, and adjusted them to a new speed of encounter, the world rushing by the windows.” “Cinema can be imagined as a hybrid of railroad and photography,” Rebecca Solnit wrote in her superb book River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West. And it is impossible to see the rails spooling under the wheels without thinking of the film strip running through the projector, frame by frame instead of tie by tie, sprocket holes engaging instead of driving-wheels churning, but the same linear, flowing movement. The effect of the resulting films is not so much like being on a train as it is like being a train, swallowing up the tracks as you hurtle through space. It wasn’t long before early cameras, too big and unwieldy to be easily moved, were being placed at the front of locomotives traveling through scenic landscapes. The best-remembered of the “actualities” in the Lumière Brothers’ first program of projected films in 1895 recorded a train pulling into a station-allegedly causing audience members to faint or flee, though it does not even approach the viewer head-on, but cuts diagonally across the screen, rolling to a gentle halt.

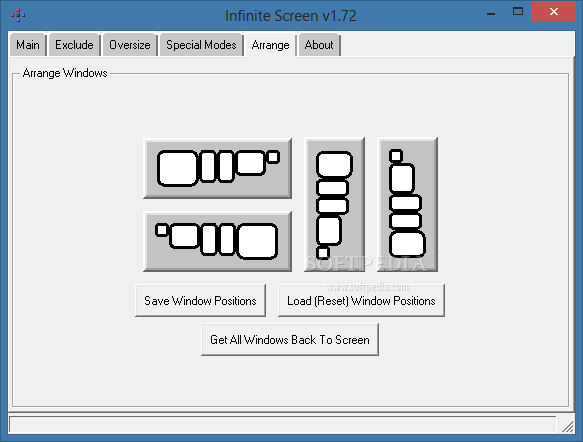

Infinite screen tunnel movie#

The train and the movie camera were lovers from the start.

The Hidden City screens Wednesday, February 6 at Film Society of Lincoln Center as part of Film Comment Selects

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)